Contemporary India, even more than in the past, is – quoting Winston Churchill – like “a riddle wrapped in a mystery that lies within a contradiction.”

Contradiction is the key word to describe the current status of India and the direction to which its development in the future will move: contradiction between an increasingly important international position and a delicate internal fragility; contradiction between a national identity shown by the country in front of the rest of the world and a varied ethnic and cultural heterogeneity often carrier of tensions; contradiction between the new, important opportunities that the world offers and grasps from an India increasingly open and the hardships met by the New Delhi government while perpetrating the long-standing rivalry with Pakistan, abundantly returned by Islamabad.

No contradiction, however, between the geographical breadth of India and the extension of the inequalities and socio-economic dimorphism inside it: within the only, large time zone of the country, but also within different neighborhoods of cities like Delhi, Kolkata and Mumbai, we may encounter different historical “time zone” relative to the population standard of living and the possibilities of access to essential services and opportunities which is granted them.

These opposing impulses have a primary reflection on the conduct of the Indian government and the policies implemented by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his ministers both internally as internationally.

In recent years, New Delhi has developed an active international strategy that reflects the growing importance of India under a political and economical point of view, and the increasing scale covered by the scenario in which the geopolitical strategy of the country unfolds.

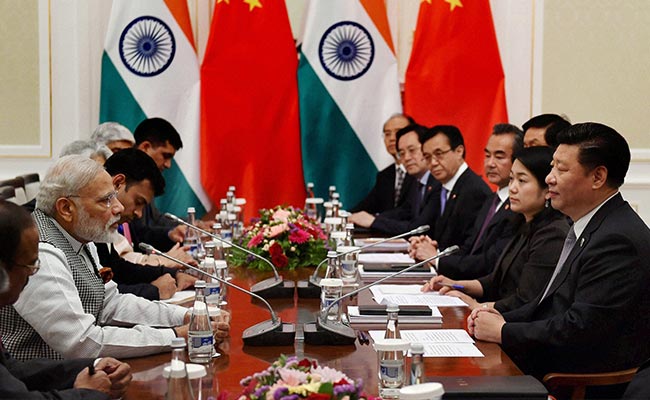

Addressing new operational challenges the government of the Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has found itself in a very peculiar situation, which saw a direct connection between the new interests of India and the traditional geopolitical issues of the country, related to the historical confrontation with neighboring Pakistan and the difficult relationship with China, with which India cultivates a contradictory relationship of economic integration and geopolitical unrest.

The great interest of China to the Indian Ocean was often viewed with suspicion by the last governments of New Delhi. India sees over 80% of its trade pass on oceanic routes, and thus in turn, owns a high interest in the protection of the “maritime highway” and the preservation of its interests. In recent years India has designed a geopolitical strategy to balance China’s growing influence in the Indian Ocean.

To counterbalance the Chinese approach to many Asian and African countries in the Indian Ocean – such as Sri Lanka and Kenya – India’s action plan aimed at building closer ties of similar nature with States “complementary” to those entered into the orbit of the People’s Republic: for instance tightening solid ties with Seychelles and Mauritius through the encouragement of economic and political cooperation.

Recently, the Indian government has scored a point in its favor being able to convince Maldives, Seychelles and Mauritius to develop in their territory a number of radar installations, for a total of 32 plants which, once completed, would permit the Indian armed forces to control the movement of any vessel operating in the oceanic basin.

Directly related to the ambitions of Beijing and New Delhi on the ocean routes is the current race for naval rearmament that put to work India and China: in the case of India, the backbone of the project are the aircraft carriers, which, according to the “2007 Maritime Capabilites Perspective Plan” (yes, the times of India are very long …), will be finalized with a net operational increment of the Indian fleet, which will be able to protect its maritime commercial traffic and defend the coastal areas of the country.

The Indian weapons program is intense and well structured, although slow: in July 2015 was launched a plan of 61 billion dollars which, in twelve years, will bring the Indian fleet to increase its size by 50%, deploying as many as 41 new vessels. Among these, the most significant investment will be aimed at creating the “Vikrant” and the “Vishat”, two large aircraft carriers that will support the Soviet-built “Vikramaditya (yes, it is still operating), and will represent the main effort of the Indian naval shipbuilding. The “Vikrant” will enter service in 2018, while the “Vishat”, which should be completed by 2025, will be the first Indian carrier powered by nuclear energy.

While continuing their strategic rivalry, however, China and India keep open an important diplomatic channel insisting on the possibility of carrying out projects strategically convenient to both despite all: discussions are continuing on a regular basis to take forward the regional integration project of the “BCIM corridor” (Bangladesh, China, India, Myanmar) which will link Kolkata with Kuming and will affect an area of over 1.5 million square kilometers.

The “BCIM corridor” was defined by Prem Sankar Jha – among the greatest scholars of the relationship between Beijing and New Delhi – as the best chance to avoid that India lose the opportunity to benefit from the connectivity project “One Belt, One Road” and the economic benefits associated with it, while Xi Jinping and Narendra Modi have decided to speed up the process that will lead to launch the first infrastructural works.

The project is the eastern equivalent of the “China-Pakistan Economic Corridor” (CPEC), which at the same time is viewed with suspect by India, as it is considered the vehicle to strengthening the geopolitical axis between two historically allied countries and in turn competitors with New Delhi, and whose implementation is the major obstacle for the effective success of the same “BCIM corridor”.

India, in fact, while is maintaining this complex relationship with China, on the other hand it is in a phase of acute stress in the relations with its western neighbor. In particular, Pakistan is accused by New Delhi to persevere in military provocations in the disputed area of Kashmir and blamed to have indirectly endorsed the attack performed last September 18th by a group of terrorists belonging to the Jaish-e-Mohammed group against an Indian border post, in which 17 soldiers were brutally killed.

Pakistan has been called by Modi “mothership of terrorism”, and from September to today between Islamabad and New Delhi fell a frost that brings to mind the times of War known by the two countries in the past but to which could obviate in the long-term the simultaneous entry in 2017 of India and Pakistan in the “Shanghai Cooperation Organization”, which includes Russia, China, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan. Again China acts as a binder for Asia and increasingly is worthy of being considered the World’s number one power.

However, it is a positive and active India the one which fits in the Asian and Oceanic geopolitical context, an India which in any case must not forget, in the course of its development process, the continuous occurrence of numerous issues that expose much internal social fragility. This has reappeared in a particularly intense way in the context of the recent monetary maneuvers conducted by the Indian government. On November 8, with the declared intention to decapitate the circulation of money in the “submerged economy” and boot the passage to the digitization of the system and a “cashless economy” (in essence, an economy completely placed under the eye of the “Big Brother” ATM circuit), the government imposed the withdrawal from circulation of all the 500 and 1000 rupees banknotes, representing the vast majority of the legal tender in the country. This has led to the disappearance from the circulation of approximately 80% of cash, inflicting serious injury to domestic movements in the Indian economy and, above all, to the spending possibilities of the population, which had to face several problems in the conversion of banknotes into notes still having legal value or into the newly released 500 and 2000 rupees notes. This has placed the government in face of the reality: the policy has been too drastic and radical, a silly childish policy. In fact, illiterate with “hand to mouth” economy have died line up in front of banks, trying to change the few banknotes in their possession, while banks within few days turned without available cash and had to shut the gates. Other desperate tried to pay for medical expenses with their meager savings in cash, seeing themselves reject out of hospitals with no future but die as beasts. Meanwhile fatties billionaires paid their bribes to senior officials of the same Government with bank transfers from their offshore accounts.

For better or for worse India always remains an unknown factor in world geopolitics and we keep talking about it.

Source: Gli occhi della guerra

More to read: 100 days of demonetisation: Stories of hardship under BJP awkward policy