The interesting history of Chongryon and the mass exodus to the DPRK. Thanks to NK News.

In December 1959, the first group of ethnic Koreans from Japan boarded a Soviet ship in Niigata. The atmosphere aboard was festive, and the ship’s destination was the North Korean city of Wonsan.

Thus began the massive repatriation of ethnic Koreans from Japan to North Korea. It continued up until 1984, and between 1959 and 1984 period some 95,000 Koreans moved to what they called the “land of their ancestors.”

This massive exodus of ethnic Koreans from capitalist Japan attracted much attention worldwide. It was already more or less universally accepted that spontaneous migration was certain to drive people from the communist bloc to the embrace of capitalism, and not vice versa: take the massive migration from East Germany in the 1950s, or the exodus from Hungary after the suppression of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution.

So many people across the world were surprised, perplexed, annoyed or delighted (depending on their political persuasions) to see nearly 100,000 people move to the easternmost state of the communist bloc.

To understand why this happened, one needs to look at the bizarre world of Japanese politics of the 1950s, and trace the history of ethnic Koreans in Japan – or Zainichi Koreans as they are frequently called.

MIGRATION TO JAPAN

While Japan and Korea are neighbors, for centuries both countries enforced what we now would describe as a ‘strict immigration control’, banning long-term settlement of foreigners and, especially, their integration into local society. In the days of the Tokugawa shogunate, until 1868, Koreans could visit Japan only on official missions, and could not settle there.

Old restrictions collapsed in the late 19th century with the arrival of Western imperialism, and from around 1880 a small number of Koreans began to move to Japan. But migration remained discouraged by Imperial authorities even when Korean became a Japanese colony.

In 1930, Tokyo’s attitude changed, and Zainichi Koreans began to be welcomed as cheap labor. Modern Korean nationalist mythologies, especially popular in North Korea, usually present 1930s migration as involuntary, but in most cases Koreans went to Japan not because they were ordered, but because they were attracted by higher wages and an abundance of unskilled and semi-skilled jobs.

By 1945 some two and half million Koreans resided in Japan, the vast majority of which were recent arrivals. Only a handful of them came from the area which became North Korea in 1945: Koreans from the North, if they wished to leave the country, usually moved to China and Manchuria, and ethnic Koreans of Japan overwhelmingly came from the southern part of the peninsula.

MADE STATELESS

The collapse of the colonial regime in 1945 prompted a majority of Koreans to return to their newly independent home country – usually because they lost their jobs in military-related industries. Nonetheless, some stayed in Japan, and by the late 1950s there were some 600,000 ethnic Koreans in the country.

In Japan, they found themselves in a difficult situation: to the Japanese public and the Japanese government, they remained suspicious and unwelcome outsiders. Japanese politicians (supported by a significant part of the general public) did not want Koreans to assimilate but preferred to keep them at a distance.

In 1947, the Allied command, still in power in occupied Japan, decided to treat Koreans, all of whom had been subjects of the Japanese Empire before 1945, as foreign nationals, and in 1952 the newly established Japanese government confirmed this: the Zainichi Koreans were stateless.

This official and nonofficial discrimination pushed the most entrepreneurial members of the community to black market and semi-legal industries, with pachinko, a kind of gambling, being particularly common. It was the only survival strategy for ethnic Koreans, who were denied access to the closed off world of Japan’s business elite, but it had a predictable impact on their perception in the country. Of course, the majority of them were not running gambling saloons, but rather toiled away in unskilled, poorly paid jobs at the margins of the Japanese economy.

SPLITTERS

The politics of the Zainichi Korean community became much more radicalized. The Japanese Communists, staunch enemies of racism and active defenders of the Japanese working class, took the Koreans under their wing. Not all ethnic Koreans were happy about this: while the majority of the politically active Zainichi Koreans were staunch supporters of the radical left, their radicalism was spiced with Korean nationalism: they looked at the Japanese, Communist or not, with a measure of suspicion.

The early 1950s were marked by arguments and clashes between Korean radicals who, loyal to the then-standard communist approach, believed that the Korean communists in Japan should join the Japanese Communist Party, and communist-nationalists who demanded an organization of their own.

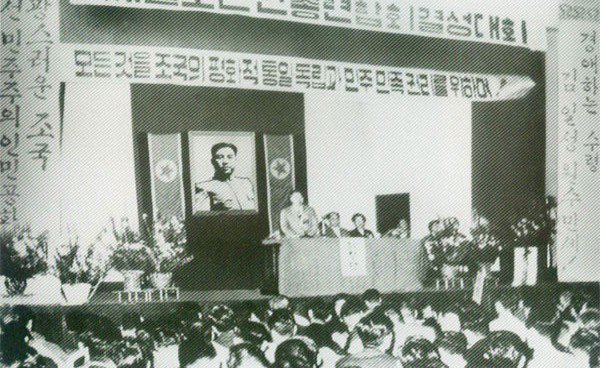

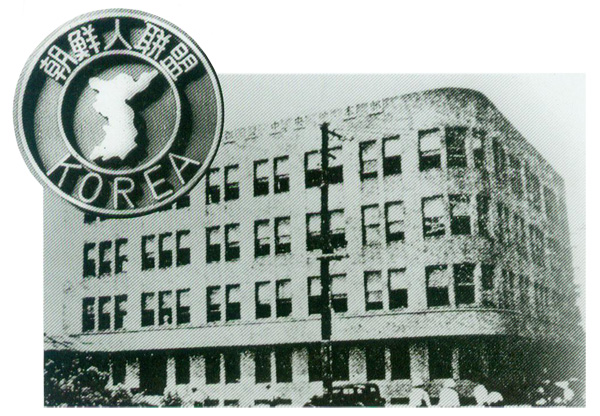

The latter group won, and in 1955 a staunchly pro-Pyongyang ‘General Association of Korean Residents in Japan’, usually abbreviated to Chongryon, came into being. Chongryon was, essentially, an overseas arm of the Korean Workers Party. Chongryon rules implied that any Korean who joined the organization became an overseas citizen of North Korea – even though this legal standing was never fully recognized by Japanese authorities.

Initially, Koreans in Japan joined Chongryon in large numbers, and for a while the Zainichi Korean community was decisively red. By 1960, some 400,000 ethnic Koreans were members of Chongryon.

For few decades, Chongryon ran a state-within-state. It collected taxes (technically voluntarily, but actually obligatory payments), run a large network of schools, and provided discriminated Koreans with legal advice, protection and a measure of political representation.

It did not help that, at the time, the Seoul government ignored the Zainichi Korean community. There was a pro-Seoul group known as Mindan, but it received only limited support from Seoul and remained marginal until the 1970s.

THE EXODUS BEGINS

In the late 1950s one of Chongryon’s objectives was to send as many Zainichi Koreans as possible to the motherland in North Korea. It was officially stated that Chongryon Koreans had no place in Japan, and should gradually move back to the DPRK where the great socialist construction was under way.

It did not matter that over 90% of all Zainichi Koreans were from the South, not North. This was a part of Pyongyang’s policy: after the Korean War, the North Korean economy badly needed workers, especially skilled workers, and many of the Zainichi Koreans had valuable skills. A massive return campaign began, led by Chongryon activists and sponsored by Pyongyang.

Right-leaning Japanese politicians also wanted Koreans to leave. As demonstrated by recent studies by Tessa Morris-Suzuki, whose scholarly but highly readable book ‘Exodus to North Korea’ is the best introduction to the subject, the Japanese political elite did not mind if the troublesome Koreans moved to what they naively saw as a paradise. The Japanese government entered clandestine talks aimed at facilitating the exodus, and promoted the idea with enthusiasm.

Negotiations began in 1955, attended by representatives of the Japanese government, the Japanese Red Cross, the North Korean Red Cross and the International Committee of the Red Cross. These talks went well, since all parties, in spite of mutual distrust and even hatred, shared one common goal: they wanted as many Zainichi Koreans as possible to leave Japan as soon as possible.

In 1959 a Soviet ship arrived at Niigata to take the first group of ‘returnees’. It was a rather misleading term, since the majority of them had never been in North Korean before, and some of them were even ethnic Japanese, wives of Zainichi Koreans who chose to follow their husbands to the unknown.

Massive migration lasted for 3-4 years: a majority of the total 93,340 that would move to North Korea did so between 1960 and 1963. But these few years would have a massive impact on North Korean society.